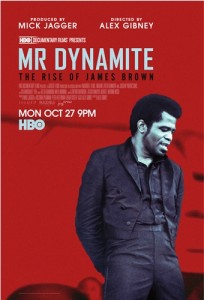

Gisteravond zond omroep NTR in Het Uur van De Wolf de HBO-documentaire ‘Mr. Dynamite:The Rise of James Brown’ uit. Een prachtig portret van de ‘hardest working man in show business’, vrijwel zonder negatieve ondertoon vanwege strafrechtelijke affaires van James Brown. Aan het woord komen onder andere voormalige bandleden, journalisten, Roots-drummer Questlove en Mick Jagger, de producent van de documentaire.

Gisteravond zond omroep NTR in Het Uur van De Wolf de HBO-documentaire ‘Mr. Dynamite:The Rise of James Brown’ uit. Een prachtig portret van de ‘hardest working man in show business’, vrijwel zonder negatieve ondertoon vanwege strafrechtelijke affaires van James Brown. Aan het woord komen onder andere voormalige bandleden, journalisten, Roots-drummer Questlove en Mick Jagger, de producent van de documentaire.

Tijdens het in Nederland gehouden documentairefestival IDFA werd ‘Mr. Dynamite: The Rise of James Brown’ op 27 november 2014 vertoond in de Rabo-zaal van de Melkweg. Edwin van Andel, bij het IDFA verantwoordelijk voor de selectie van muziekdocumentaires, zegt hierover: “Mr. Dynamite was een last minute toevoeging aan onze selectie. We vonden het belang van de documentaire en dat we deze als première konden doen belangrijk genoeg. Een mooi degelijk portret van een belangrijk artiest mocht niet op IDFA ontbreken. We hadden dit jaar veel zwarte muziekdocu’s, met oa Finding Fela, Time is Illmatic & The Case of the Three Sided Dream (over Roland Kirk) en de godfather of soul paste prachtig in dit rijtje.”

De film was in oktober 2014 al te zien in Amerika. In het artikel ”9 Things We Learned From ‘Mr. Dynamite” zette het Amerikaanse muziektijdschrift Rolling Stone toen de meest opvallende punten uit de documentaire op een rijtje.

1. His definition of “soul music” wasn’t just musical

Asked to define soul music early in the film, Brown responds, “It’s the word ‘Can’t’ that makes you a soul singer. A black man…has had extra hard knocks and he’s lived with the word ‘Can’t’ for so long, so every time he can sing about it, it comes out a little bit stronger.” Later on, Brown will expand on this definition as it related to the civil rights movement to which he was so closely tied. “Soul is when a man has to struggle all his life to be equal to another man,” said the singer. “Soul is when a man pays taxes and still he comes up second. Soul is when a man is judged not for what they do, but what color they are.”2. He was the antithesis to what was considered “beautiful”

According to friend Al Sharpton, who knew the singer for decades, Brown told him how not fitting into a traditional leading man role forced him to work harder at his craft. “James said, ‘You have to remember, Reverend, when I was coming up, you had to be tall, light-skinned [and with] long, wavy hair like Jackie [Wilson] or Smokey Robinson,'” said Al Sharpton. “‘I was short, had African features and I didn’t have any of what was considered beautiful at that time. I was determined I was going to out-dance and out-sing everybody out there and I was going to work every night.'”3. Brown’s support for Nixon was hardly mutual

Despite backing Hubert Humphrey in his failed 1968 bid for presidency against Richard Nixon, Brown openly campaigned for and endorsed Nixon in the 1972 presidential election. Many in the black community turned against Brown — “Has James Brown Sold Black People Out or Sold Them In?,” reads one headline in the film — with some going so far as to burn his albums. In one scene, Brown is heard asking Nixon to support a national holiday for Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday. “We’re examining what could be appropriate,” replied Nixon. “Good luck and much success to you.” In private, though, Nixon was less cordial. “No more black stuff,” the president can be heard saying via vintage audio tapes. “Too much black stuff. No more blacks from now on; just don’t bring them in here. James Brown apparently is very popular amongst young people; he is black. Well, what am I supposed to do, just sit and talk to him or what?”4. His cape routine was influenced by a wrestlerBrown’s infamous cape routine, in which Brown’s emcee and “cape man” Danny Ray would drape the covering over the ostensibly pained singer, was directly inspired by Gorgeous George, a popular wrestler at the time. After a match, someone would throw a cape over George’s shoulders; Brown began to incorporate the bit into his show, falling to his knees in anguish. “He sees something clicking with the crowd, that’s what it’s gonna be,” said Ray. “You don’t take that out. He said, ‘You know, Mr. Ray? This gotta stay. You got another job now.'” Added Sharpton: “It was definitely an apotheosis [of the show]. You’re distraught to where you just collapse, but somehow the strength sweeps you up and then you rise like a phoenix again.”

5. Drummer Melvin Parker once pulled a gun on Brown

Guns weren’t uncommon in a time of shady business deals and even shadier industry figures. Usually, this meant promoters and label employees, but drummer Melvin Parker also needed a weapon to show his boss force. “It didn’t matter where I was, I was always strapped,” said Parker. “Because sometimes James had good days; sometimes he had bad days. I didn’t want to be a part of the bad days.”Parker recalls the story of him and brother Maceo being summoned to Brown’s dressing room in Minneapolis. Thinking that the latter was talking behind his back, Brown began to lunge at the musician and cock his fist. “I pushed Maceo to the side, went in my pocket and pulled [my gun] out,” said Melvin. “When you have that automatic, you always keep one in the chamber. I let him know it was loaded…and stuck it right in his nose and said, ‘I’m ready now. What do you want to do, huh?! What do you want to do?!’ He put his hands up and said, ‘Naw, naw, naw, naw. I didn’t mean that. Not like that.’ I said, ‘You don’t come for me. You don’t come for my brother.'”

6. Brown preferred calling people “Mister” over their first name due to his upbringing

Despite the familial, congenial nature of the band, Brown insisted on using “Mr.” and “Ms.” rather than each member’s first name. “He said, ‘Alan, where I grew up, when I grew up, I was always Jimmy,'” said Brown’s publicity director and tour manager Alan Leeds. “‘My name ain’t never been Jimmy. If they wouldn’t call me James, you knew they really weren’t going to call me Mister. But I reached a point where if you wanted to do business with me, you had to call me Mister. And the only way to do that is set the example.’ I realized how that really had contributed to his relationships with white people, particularly in the south who controlled a lot of the venues.”7. “Cold Sweat” was inspired by Miles Davis and a series of Brown’s grunts

In 1967, Brown recorded the Pee Wee Ellis-written track “Cold Sweat,” often cited as one of the first funk songs. According to Ellis, the track’s famed bass line emulated Brown’s series of dictated grunts. “After a gig somewhere, James Brown called me into his dressing room…and said, ‘I got an idea,'” said Ellis. “Write this down.” Brown proceeded to grunt rhythmically while Ellis scrambled to find paper. “I started putting notations to his grunts which came out [as] the bass line to ‘Cold Sweat.’ I had [also] been listening to Miles Davis and ‘So What’ popped up in my head. I took [part of the horns] and just repeated it over and over. I didn’t write it to be so monumental, but my jazz influence was creeping into his R&B so the combination of the two is where funk came from.” The song would later become fodder for countless hip-hop samples.8. Contrary to legend, Mick Jagger wasn’t “devastated and traumatized” at seeing Brown’s T.A.M.I. performance

The Rolling Stones had the unenviable task of following Brown at 1964’s influential The T.A.M.I. Show, in which Brown’s 18-minute performance is one of the most electrifying in rock history. Keith Richards famously told one interviewer, “[Following James Brown] was the biggest mistake of our career,” but according to Jagger, what you see on film was not exactly what went down onstage. “That’s bullshit because the whole place was cleared and they re-lit the whole thing,” said the Rolling Stones singer after it was noted that he was “devastated and traumatized” after seeing Brown’s set. “There was another audience of screaming teenage girls. I don’t think they’d even seen James Brown and it was hours later. If you watch the film, you see us up against him and you go, ‘Well, they’re not quite as good as James Brown,’ but whatever.'”9. Clyde Stubblefield hated “Funky Drummer”“Funky Drummer,” the song that launched a thousand hip-hop tracks, has many fans — but its own drummer isn’t one of them. “I hate that song,” Stubblefield said while making a gagging sound. “We had been playing somewhere the night before and as we get to Cincinnati to check in to the hotel to go to bed, Brown said, ‘Go take them to the studio.’ We all were so tired; didn’t even want to record. So I started playing just a drum pattern. Brown liked it and we recorded it.”As Questlove notes, “Funky Drummer,” despite later becoming the template for an entire genre, was Brown’s only failed single.